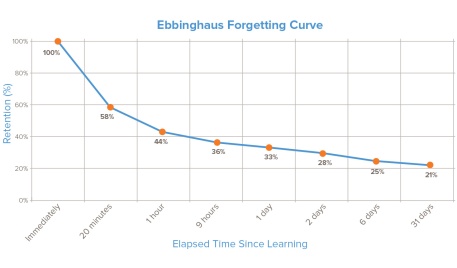

The Ebbinghaus Forgetting Curve is one of the best-known results in learning theory. The Curve demonstrates that what humans remember after a learning event drops steeply soon after completion of the event. In fact, within a month, they will forget up to 80% of what they have learned:

So, what do we mean when we say this result is a “myth?” Certainly, Ebbinghaus was a well-regarded German psychologist (1850 – 1909), and without a doubt he produced his forgetting curve in 1885. And we all know from personal experience that we rapidly forget much of what we have learned. So why would this be considered a “myth?”

As with many results in cognitive psychology it’s important to look at the actual research and consider how generalizable the result is:

- Question: How large was Ebbinghaus’s sample size?

Answer: It was one (himself).

- Question: What did he attempt to learn?

Answer: Three letter nonsense syllables (e.g ZOF).

A sample size of one is not a sufficient sample size for a rigorous experiment, and more importantly, it’s difficult for just about anyone to remember nonsense syllables for an extended period of time (see points 2-4 below).

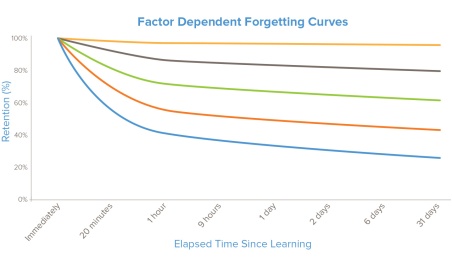

It turns out that there are a number of factors that affect our ability to remember what we have learned. Among them are:

- Individual differences. Some people are just better at remembering than others.

- Prior knowledge. Having prior related knowledge will affect our ability to remember. For example, if we ask two students learning Spanish to memorize a list of vocabulary words and one of those students is a native Italian speaker and the other is a native Mandarin speaker then, all else being equal, it will be much easier for the Italian speaker to remember the vocabulary because of the similarities of the languages.

- Importance. If someone is told that his or her job depends on knowing something and that person uses that knowledge frequently on the job then he or she will retain the new knowledge much more effectively.

- Prior learning schema. We learn best when we can situate new knowledge into prior knowledge (schemas). For example, if someone tells you that a “Dog is a mammal” but you have never seen a dog and do not know what a mammal is, you are unlikely to remember this fact for very long. But if you are well acquainted with dogs, and you know that a mammal is an animal with warm blood and fur or hair, you can fit this new information into your existing schema for mammal and are much more likely to remember this fact. This is the reason we organize instruction from the general (help the learner create a broad schema) to the particular (help the leaner fit new knowledge into the preexisting schema).

- Repetition. How often is the learner exposed to this new information? Just once or several times, spaced over a period of days or weeks?

- Retrieval. Is the learner required to retrieve and use this knowledge periodically?

All of these factors contribute to learning retention. Depending on which factors are active we actually have a series of forgetting curves, not a single, absolute curve:

So, it is true that our learners forget, but they do so at different rates, depending on the circumstances.

As we will see in this series much of what we believe to be true about learning is not so much flat out wrong, as it is oversimplified, overgeneralized and hyped by those who benefit from doing so.

Yes, the learning curve does depend on several factors, and the situation you cited was more of a case study than full research based on the population size, but there may be a point to the case study, however, since the brain is not static, but ever-changing based on environmental and behavior influences learning retention as well as the learner‘s neurons, which are organized into three types of layers, we might be able to explain the learning process as input, hidden and output layers that will improve retention. But this general proposition may be individually based, it is part of all individual’s neuronal network, so retention (e.g. memory) is a factor depending on individual motivation. So, the question becomes how do we increase learner motivation to improve learner retention?

LikeLike